Why Their News Is Bad News – CPBF Programme from 1983

Last week, Better Media was given access to a copy of a TV programme made by the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom, our predecessor organisation. Titled ‘Why Their News Is Bad News’, the programme was made for the BBC’s Open Door series of community-made features. Unfortunately, we are not allowed to publish the programme, but we found it fascinating and wanted to share some highlights.

Before we get into it though, we should thank the good people at the Bishopsgate Institute for providing us with the programme. Why Their News Is Bad News features as part of the exhibition People Make Television, which explores and celebrates community access television in the UK during the 1970s. It features more than 100 programmes made by campaigning and community groups and broadcast on the BBC and local community cable channels. Check out the exhibition at the Raven Row gallery in Spitalfields until 26th March.

Why Their News Is Bad News – hosted by filmstars Julie Andrews and Julie Christie, if you can believe it – opens with a look at BBC coverage of the ASLEF train drivers’ strikes in the early ’80s. It’s an extremely pertinent analysis, given the adverse coverage that ongoing rail strikes have faced over the past year.

In studying BBC coverage during the period of that ASLEF strike, the CPBF noticed a trend: the beeb prioritised the perspective of British Rail management and gave minimal airtime to the views of striking workers. Sound familiar? They also shifted the focus of discussion from the actual demands of the dispute to one question: how many drivers were breaking the strike and going back to work? Figures from British Rail that addressed this question were obsessively examined and re-examined, and the CPBF’s analysis showed that there seemed to be little regard for the consistency and accuracy of these figures.

Back in 2023, the BBC have employed a similar device, refocusing their coverage around a new question: how much are rail workers paid? With each day of strikes, new headlines and subheads reinterrogate this supposedly innocent question. We are told this is simply a ‘fact check’, examining the claims of politicians and unions alike. But with this continued relitigation in almost every BBC News article, the overall effect is the same as it was in 1983: the BBC seeks to reduce the discussion to a simple question of pay figures, orienting it around a focal point that suits the establishment, rather than the many valid criticisms raised by the strikers.

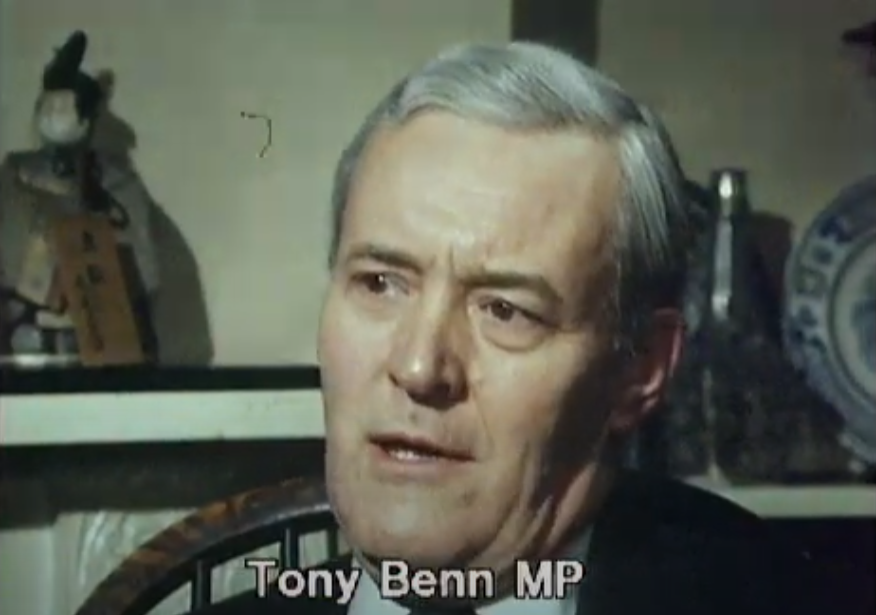

Tony Benn MP appears multiple times in the programme. In a BBC interview conducted after the executive elections at the 1982 Labour party conference, in which the left of the party suffered some defeats, Benn makes clear his feelings about the influence of the broadcaster:

Interviewer: “A setback for the left, Mr Benn? […] Why do you think it’s happened, do you think the trade unions have seen the electoral damage that might be done [by the left]?”

Benn: “No, I think probably this is a victory for the BBC, who’ve been denouncing good socialists in the Labour party for a year.”

Again, the parallels to recent events are clear.

One of the more subtle issues the programme addresses is the move towards ‘consensus’ as a key principle of BBC broadcasting. As Christie puts it, “In a lot of the ASLEF coverage, the underlying message was that the strike was going against the ‘National Interest'”. This notion of a single consensus opinion held by the British public is part and parcel of most mainstream media messaging in the 21st century, but in 1983 it was a newer trend, and its failings were more apparent to many. This assumed consensus is a centrist one – the programme notes that the views of those on the centre-right of the Labour party and centre-left-leaning Tories are given significant billing by the BBC, even though the latter were a small minority in Thatcher’s party at the time.

Why Their News Is Bad News provides a short-form but decisive dismantling of this idea that the broadcast media should speak to the consensus of the public, to ‘what we can all agree on’. To assume a ‘National Interest’ is simply to downplay and dismiss the importance of the many personal and political perspectives that exist amongst the viewing public – especially those that are already marginalised by the structures of the state. Most modern arguments about media reform focus on issues of ownership, malpractice and corruption, but this programme provides a welcome reminder that the broader philosophical questions of what it is to produce mass media are still extremely relevant and worth addressing.

It’s a real shame that we’re not able to share the programme in full, but we hope this short overview has communicated some of its insights. We highly recommend that you visit the exhibition at Raven Row if you are able to, to see this and many other gems from the history of community television.